ZLATYU BOYAJIEV’ PERMANENT EXHIBITION

(Stoyan Chomakov House), 18 Saborna Street

The exhibition displaying the work of the great artist Zlatyu Boyadjiev (1903 – 1976) was opened in 1980 in this representative period-house. The multitude of canvases, some of imposing size, is displayed in all rooms of the big two-storey house. In the courtyard in front of the house there is monument to the honoured artist .

The noble Revival house, where the exhibition has been set out, was built for Dr. Stoyan Chomakov in 1860. It was a very modern-looking house for its time although it was a solid sym-metrically designed building with facades decorated in the classical style widely spread in Europe at the time. Dr.Chomakov was one of the first academically trained physicians in Plovdiv and was a champion for an autonomous Bulgarian church in the Revival bulgaria private tours.

After the Liberation the heirs gave the house as a present to King Ferdinand. In the 50s of the 20th c. it housed a branch of the Ivan Vazov Public Library until the time it was entirely renovated and given over for the setting up of the exhibition of the works by Zlatyu Boyadjiev.

‘GEORGI BOJILOV – SLONA’ PERMANENT EXHIBITION

(Skobelev House), 1 Knyaz Tseretelev Street

This Revival house is adjacent to the Hippocrates Pharmacy. Kostadin Kaftanjiyata, a Bulgarian from the town of Stara Zagora, built it in the 60s of the 19th century. In the years after the Liberation and until her death here lived Olga Sko- beleva (1823 -1880), mother of the Russian General Skobelev. She became known for her charity work in aid of the victims of the Turkish atrocities in South Bulgaria during the April Rising and the Liberation War. In gratitude for her concern for the orphaned children in Thrace, the Bulgarians have called her ‘Mother Skobeleva’. A memorial park has been dedicated to her off the Istanbul highway in the outskirts of Plovdiv.

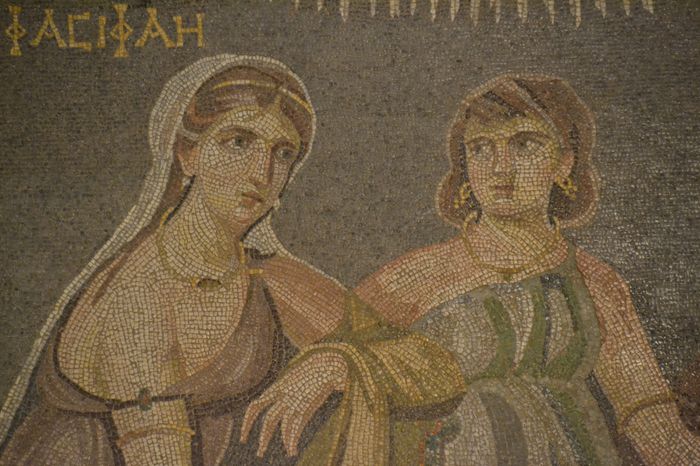

At present the house is occupied by the Plovdiv branch of the ‘Future for Bulgaria’ Foundation. It was with the contribution of the foundation that in 2003 a permanent exhibition of the work of the prominent artist Georgi Bojilov-Slona was arranged. The end-wall of the house, facing Saborna Street is decorated with a commemorative panel dedicated to the artist and executed in paintings and mosaics to the design of Dimiter Kirov.

Apart from the period houses of great artistic and architectural value, Old Plovdiv possesses some buildings of lesser architectural merit but associated with significant events in the past. These are historic places marked with commemorative inscriptions. On Saborna Street opposite the Holy Virgin Cathedral stands the house of Dr. Rashko Petrov, a physician with a medical degree and a prominent revolutionary, who participated in the First Bulgarian Legion in Belgrade in 1862.

There he became friends with Vasil Levski – the ‘Apostle of Liberty’, who often stayed at Dr. Petrov’s house when in Plovdiv. Right after the Liberation War in 1878 the house was the seat of the interim Russian representation headed by the Imperial Commissioner Prince Alexander Dondukov-Korsakov. Next-door to Dr Rashko’s place is the house where Dr Konstantin Stoilov, an eminent Bulgarian politician and statesman, Prime Minister of Bulgaria from 1894 to 1899, was born.